jacksondwj.com – Herbert Hoover, the 31st President of the United States, often evokes a mixed reaction when it comes to his economic policies. His presidency, which spanned from 1929 to 1933, coincided with the most severe economic downturn in modern American history—the Great Depression. While Hoover entered office with high hopes of continuing the economic prosperity of the 1920s, his tenure is largely defined by the economic collapse that would come to shape his legacy. Despite his failure to prevent the Great Depression from worsening, Hoover’s economic policies were rooted in an optimistic belief in self-reliance, the power of private industry, and government intervention only when absolutely necessary.

This article examines Hoover’s economic policies, evaluating both their successes and their failures. It explores his approaches to business regulation, economic expansion, the banking system, and the social welfare system, while also considering the broader political climate that influenced his decisions. Ultimately, Hoover’s economic policies represent a clash between classical economic theory, limited government intervention, and the reality of a massive, global economic crisis.

The Roaring Twenties: Hoover’s Economic Philosophy Before the Crash

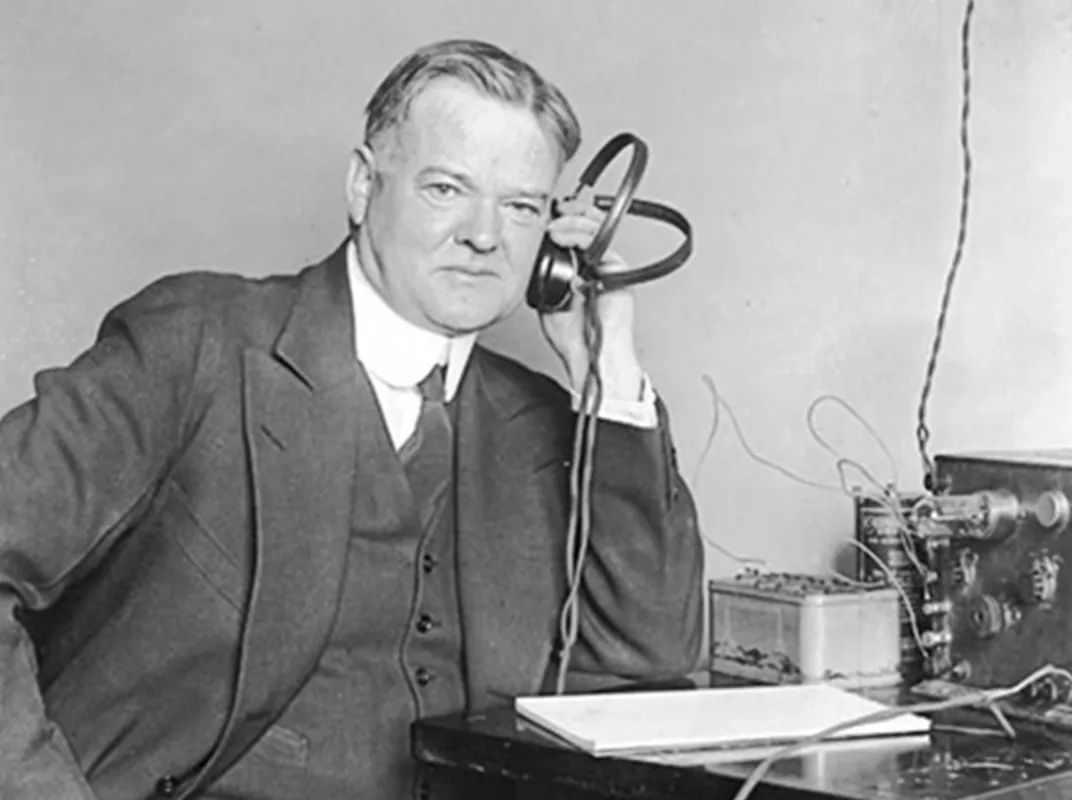

Herbert Hoover’s rise to the presidency in 1928 came during a period of tremendous economic growth. The 1920s, known as the “Roaring Twenties,” was a decade marked by innovation, industrialization, and a booming stock market. Hoover, a former engineer and successful businessman, entered the White House with a deep belief in the power of industry, efficiency, and cooperation between government and business.

As Secretary of Commerce under Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, Hoover had been instrumental in promoting business expansion and maintaining economic stability through voluntary cooperation between government and private sector leaders. He advocated for a system where industry and labor could work together to solve problems without heavy-handed government intervention. Hoover’s confidence in this model was bolstered by his belief that America’s prosperity was sustainable, and he believed that government could play a positive, but limited, role in fostering an environment conducive to economic growth.

Hoover’s economic policies before his presidency were characterized by his belief in “voluntary cooperation”—a system where businesses would self-regulate and collaborate with the government to maintain stability. He saw the government’s role as providing guidance and support rather than direct intervention. This hands-off approach reflected Hoover’s belief in the fundamental soundness of the American economy and his faith that private industry could be trusted to maintain prosperity.

Economic Success Before the Crash

Under Hoover’s leadership as Secretary of Commerce, the U.S. saw some notable successes. He helped to streamline industry through the creation of organizations that facilitated cooperation between government and business. Hoover was also instrumental in promoting agricultural innovation, as he supported the introduction of new farming techniques and better irrigation methods, which improved productivity in agriculture.

Additionally, Hoover supported the development of new infrastructure, such as roads, highways, and airports. His focus on infrastructure development was consistent with his belief in the importance of technological progress and economic efficiency. Hoover’s administrative experience gave him an understanding of how to manage large, complex systems, and he applied this knowledge to support a number of successful initiatives aimed at improving American economic competitiveness.

While Hoover’s leadership as Secretary of Commerce was marked by significant growth in various sectors, it was also a period of growing income inequality and over-speculation in the stock market. Hoover failed to foresee the potential dangers of unregulated speculation and excessive debt accumulation, particularly in the financial sector, which would contribute to the catastrophic crash that occurred just months after he assumed office in 1929.

The Stock Market Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression

The defining moment of Hoover’s presidency came in October 1929, when the Stock Market Crash triggered the onset of the Great Depression. The crash sent shockwaves through the financial system, eroding public confidence in banks, businesses, and the overall economic system. The depression worsened through the early 1930s, leading to widespread unemployment, poverty, and a dramatic decrease in industrial production. By the time Hoover took office, millions of Americans were already facing hardship, and the crisis would ultimately define his presidency.

Hoover initially underestimated the scale of the economic collapse. He believed the depression would be temporary and that the economy would rebound quickly. Hoover’s reluctance to take immediate and large-scale government action to address the crisis reflected his belief in the principles of rugged individualism—that individuals, businesses, and local governments should take responsibility for their own recovery, rather than depending on federal aid.

Hoover’s Initial Response to the Great Depression

Hoover’s early responses to the Great Depression were characterized by attempts at fostering voluntary cooperation and faith in market forces. Rather than pushing for extensive government intervention, he focused on encouraging businesses to maintain wages and employment levels, hoping that voluntary efforts would keep the economy from spiraling further downward. He also encouraged local governments to increase their spending on public works projects to create jobs and stimulate economic activity.

In addition, Hoover called for banks and other financial institutions to voluntarily reduce their debt and avoid hoarding money. He pushed for policies that would ease credit and foster international trade, such as the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act of 1930, which, though aimed at protecting American industries, inadvertently worsened the global depression by triggering retaliatory tariffs from foreign countries.

The Public Works Administration and the RFC

As the depression deepened and Hoover’s optimism proved misplaced, he reluctantly took more action. One of the most significant measures Hoover introduced was the Public Works Administration (PWA), a large-scale initiative designed to create jobs through the construction of public infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and dams. The PWA was the most ambitious federal public works program of its time, and it did provide jobs and long-term infrastructure benefits to the U.S.

Another key response was the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1932. The RFC was a federal agency designed to provide loans to banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions to stabilize the financial system. Hoover believed that by providing loans to struggling institutions, the RFC could shore up the financial system and prevent further collapses. While the RFC helped some institutions survive the crisis, it failed to reach the broader population of struggling farmers and unemployed workers, and many criticized Hoover for prioritizing the interests of large corporations and banks over ordinary citizens.

Failures of Hoover’s Economic Policies

Despite Hoover’s efforts, his economic policies largely failed to reverse the course of the Great Depression. Several factors contributed to the ineffectiveness of Hoover’s approach:

The Missteps of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff

One of the most widely criticized aspects of Hoover’s economic policy was his signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. Designed to protect American industries by raising tariffs on foreign goods, the act triggered a trade war with other nations, which retaliated by imposing their own tariffs on U.S. exports. As a result, global trade contracted sharply, exacerbating the economic downturn and deepening the global depression. Economists widely agree that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff worsened the economic crisis and made recovery more difficult.

Limited Federal Relief and Hoover’s Beliefs in Self-Reliance

Hoover’s belief in rugged individualism prevented him from endorsing direct federal relief for the unemployed. He believed that government assistance would create dependency, undermining the American character of self-reliance. As a result, Hoover was reluctant to provide the level of direct aid that was needed to alleviate the widespread suffering.

This reluctance became painfully evident in the Bonus Army March of 1932, when thousands of World War I veterans marched on Washington, D.C., demanding early payment of their service bonuses. Hoover’s decision to use military force to remove the protesters from their encampment alienated many Americans, further damaging his reputation and public support.

Failure to Address the Banking Crisis

Hoover also failed to act decisively to address the banking crisis that was unfolding as a result of the depression. Bank failures were widespread, and many Americans lost their savings. Hoover’s hesitation in implementing banking reforms or guaranteeing bank deposits meant that the financial system remained unstable, contributing to the erosion of public confidence.

The Road to Franklin D. Roosevelt

By the time of the 1932 election, Hoover’s economic policies had largely failed to reverse the effects of the Great Depression, and he was seen by many as out of touch with the needs of the American people. His opponent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, ran on a platform of bold government intervention and social welfare reforms, promising a “New Deal” for Americans suffering from the depression.

Roosevelt’s victory marked the end of Hoover’s presidency, but it also signified a major shift in American economic policy. FDR’s New Deal introduced sweeping reforms that expanded the role of the federal government in economic and social matters, in stark contrast to Hoover’s belief in limited government intervention.

Conclusion: The Mixed Legacy of Hoover’s Economic Policies

Herbert Hoover’s economic policies are often remembered for their failures in the face of the Great Depression. His belief in voluntary cooperation, limited government intervention, and rugged individualism left him unprepared for the scale of the crisis that unfolded during his presidency. While Hoover’s policies, such as the Public Works Administration and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, provided some relief, they were insufficient to address the widespread unemployment and poverty caused by the Depression.

Despite his failures, Hoover’s legacy is not entirely negative. His attempts at infrastructure development, as well as his initial focus on business cooperation and technological advancement, laid the groundwork for the more extensive public works programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hoover’s presidency marked a critical turning point in American economic history, illustrating the limitations of classical economic policies in the face of an unprecedented economic collapse. Hoover’s inability to combat the Great Depression was, in many ways, a precursor to the bold government intervention that would come to define Roosevelt’s approach to economic recovery.